ESG Considerations in Derivatives Markets

Researched and compiled by: Pham Duc Khiem, CFA® Institute Member & Dang Tran, FVMA®

Issued by: Finstock, Inc.

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing has become ubiquitous in stocks and bonds, but its application to derivatives – especially commodity futures – is novel. Janardanan, Qiao, and Rouwenhorst (2024) explicitly highlight that “like stocks and bonds, derivatives investments have a measurable ESG impact” . They propose a top-down ESG framework for futures: rather than scoring individual firms, one scores the underlying activities/geographies of commodities and currencies. For commodities, this means assigning each contract an E (environmental) score based on its carbon footprint, an S (social) score based on the development level of its producing countries, and a G (governance) score based on corruption indices. Concretely, they measure E as kilograms of CO₂-equivalent per dollar of investment in that commodity, S as a production-weighted Human Development Index (HDI), and G as a production-weighted Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) . For example, one portfolio selects the 50% of contracts with lowest E and finds it reduces emissions by ~81%: the benchmark’s 2.7 kg CO₂/$ falls to just 0.5 kg . A combined ESG-aware portfolio ranks contracts by the sum 2E+S+G (to weight environment more) and equally invests in the top half. This composite strategy lowers emissions by ~44% while modestly improving S and G (e.g. raising the HDI score by ~4% and the CPI by ~7% relative to the benchmark) . In each case, portfolios are fully collateralized and rebalanced annually.

»

E, S, G Metrics: In Janardanan et al.’s scheme, E reflects carbon intensity (kg CO₂ per $ invested). For example, Figure 3’s note shows E as kg CO₂_eq per dollar, S as production‐weighted HDI, and G as production-weighted CPI . Intuitively, low‐E futures are those tied to less-emissions-intensive commodities (e.g. gold or soybean vs. crude oil or natural gas). The S score promotes commodities from more developed regions, and G favors those from less-corrupt jurisdictions. By construction, the authors effectively treat futures as proxies for economic activity by region: e.g. natural gas futures get a high E score because natural gas production is carbon-intensive, while futures on metals produced in Scandinavia may earn higher S and G scores. This top-down approach contrasts with the usual firm-level ESG ratings used for equities, and it is designed to respect the role of futures as risk factors rather than direct ownership stakes.

»

Portfolio Construction: Using these scores, Janardanan et al. test two hypothetical screens. The “Eaware” portfolio simply selects the 50% of commodity futures with the lowest E ranks each year, equally weighted. The “ESG-aware” portfolio sorts by the composite ESG rank (2·E + S + G) and invests equally in the top half . The authors compare each to a standard equally-weighted (EW) commodity index. They find that the E-aware portfolio closely tracks the benchmark (monthly return correlation ≈0.88) but has a slightly lower 10-year return (about –1.3% per annum relative) . Most strikingly, its carbon footprint plummets: emissions per invested dollar drop from 2.7 kg to 0.5 kg (−81%) , achieved by underweighting high-emission commodities (e.g. natural gas, palm oil). However, focusing only on E has side effects: the S (HDI) and G (CPI) scores decline slightly (by ~2% and 4% respectively) because the screen ignores social/governance factors . By contrast, the ESG-aware portfolio achieves emissions roughly halfway (≈56%) between the EW and the pure-E portfolio, while modestly raising S and G. It retains a very high return correlation to the EW index (≈0.92) . In short, the ESG screens materially change the attributes of the commodity portfolio (much lower carbon intensity, slightly higher average HDI/CPI) but do not dramatically alter its risk/ return profile versus a broad commodity index.

Theoretical Rationale and Economic Channels

The above framework is grounded in how derivatives markets influence real-world outcomes. Unlike corporate bonds or equity – where buying a firm’s securities directly affects its cost of capital – futures represent insurance contracts or risk-sharing tools. Janardanan et al. emphasize that ESG in derivatives operates through the hedging channel: by influencing the cost of hedging for companies engaged in the relevant commodity or currency market . Put differently, an ESG-sensitive futures market could make insurance more expensive for “bad” commodities and cheaper for “good” ones. Because hedging decisions (rollover of futures hedges) occur frequently for producers and consumers, this could cumulatively mimic an ongoing ESG levy or subsidy. In their conclusion, the authors argue that “coordinated ESG policies in derivatives have the potential to make a significant impact on corporate decision-making” . Hedging a price risk is analogous to issuing debt: if the “price of insurance” (futures hedging) rises for carbon-intensive commodities, companies may invest less in that activity.

This logic has precedents. Auspice (Basnicki and Pickering) note that commodity futures do not finance production directly: “commodity futures investments do not require physical extraction… and they do not link to the environmental impact from resource extraction” . Instead, futures share risk. If speculative demand for low-ESG (carbon-heavy) futures shrinks, futures prices might move (e.g. become more backwardated), raising hedging costs for producers. This “implicit tax” on high-emission hedging could induce firms to cut emissions or seek alternatives. More generally, theory suggests that a futures market with an imbalance between longs and shorts (and now ESG preferences) could push prices to reflect ESG concerns. For example, if most consumers are long hedgers (they buy futures to lock in supply price) and fewer speculators are willing to take the short side in high-emission markets, futures prices would rise for those contracts, at least short-term. By contrast, “good” commodities could see lower futures prices and increased consumption. Such shifts parallel a risk-sharing argument: as Van Hemert et al. (2024) suggest, a long-short ESG fund could overweight good commodities (more risk sharing) and ignore bad ones

These channels are not uncontroversial. An AQR analysis warns that simply avoiding “bad” commodities (a no-touch approach) or overweighting “good” ones can distort prices and hedging. Janardanan et al. acknowledge this. As AQR notes, Janardanan’s proposal to go “more long ESG–‘good’ commodities and less long…’bad’ ones” does have side effects : if fewer market participants take long positions in a commodity, its price will tend to fall (and vice versa), altering quantities demanded. Over time, the futures market could even invert the intended ESG signal. In short, ESG integration via futures acts like adding supply/demand pressure to certain goods. Sustainable investors must consider these feedbacks: the price impact of screening might help ESG goals, but it could also simply change risk premia or invite speculative entry. The authors themselves stress that their ESG strategy “comes not without undesirable potential side effects”

Despite the complexity, the crucial theoretical point is that futures offer a lever on hedging costs, which is analogous to a continuous, global ESG subsidy/tax. By contrast with stock investing (which targets a single firm’s funding cost), derivative-based ESG “targets the cost of insurance to corporations engaged in a similar economic activity” . Because hedging is regular and common, its aggregate effect could rival corporate cost-of-capital signals.

Comparison to Other ESG Approaches

The Janardanan et al. framework is top-down and macro-driven, in contrast to the traditional bottom-up firm-based ESG screening used in equities and bonds. In commodity contexts, other approaches include:

»

Exclusion or “No-Touch” Screens: An investor might simply avoid futures on certain commodities (e.g. thermal coal, food staples) due to environmental or social concerns . This is essentially treating the futures index like a “negative screen.” The drawback is that outright exclusion can forgo risk premia and may have limited impact on underlying production (the resource still trades in spot markets). AQR notes that blanket exclusion (“no-touch”) can conflict with hedging needs: for many commodities, large producers rely on futures hedges, so forbidding those markets could reduce liquidity and transparency

»

Thematic / Tilting Strategies: Instead of outright ban, some investors might overweight “green” or “soft-commodity” exposures (e.g. timber, renewables) and underweight heavy emitters. The Janardanan et al. E-aware/ESG-aware portfolios are examples of tilting. Similarly, one could use futures on “sustainable” commodity indices (e.g. indices that exclude fossil fuels). For example, S&P Dow Jones and MSCI have researched sustainable commodities indices, though these are not yet mainstream.

»

Vertical Integration (equity vs commodity): Investors concerned with commodities might invest in producers with strong ESG rather than in commodity futures directly. This shifts the focus to stock/ bond screens in resource companies. The drawback is a tighter correlation to equity markets and potential greenwashing (as Auspice points out). It also may not capture commodity risk exposures.

»

ESG-Linked Derivatives: Outside commodities, market-makers have introduced ESG-linked swaps or options, where payouts depend on ESG KPIs (e.g. an “ESG forward” on copper that pays extra if CO₂ in copper mining falls). These are in early stages and mostly OTC. They are more experimental (see Bellanti 2023 on “ESG-Linked Derivatives”【15†】), but offer another angle: the derivative’s payoff or margin adjusts with ESG metrics, directly tying hedging costs to performance.

Potential Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

»

Preserved Liquidity and Diversification: Commodity futures markets are generally deep and liquid. Janardanan et al. find that even their ESG-screened portfolios closely track broad indices. This suggests investors can pursue ESG goals without sacrificing the liquidity and diversification of futures . Indeed, futures often have lower correlation with equity/bond markets than do commodity stocks , so ESG integration here retains diversification. Notably, CME Group now offers ESG versions of major equity futures (see below) because investors want “similar return profile” with ESG filtering , implying that ESG indices can track benchmarks closely.

»

Inflation and Risk Hedging: All portfolios (EW, E-aware, ESG-aware) maintain positive correlation with inflation, meaning they still act as inflation hedges. This is important for institutions using futures to guard against price shocks; ESG screening does not negate that role . In fact, some ESG mandates value the “societal” role of stable commodity markets (Auspice points out that futures provide risk management and liquidity to the economy ).

»

Signal to Corporations: By affecting hedging costs, this approach may influence corporate behavior. Analogous to how bond yields change with credit risk, persistent futures flow imbalances could pressure producers to decarbonize. Because hedging occurs frequently, even small premia differences can accumulate. In principle, this is a powerful signaling device: unlike a one-time green bond issue, futures hedging is ongoing.

»

Ease of Implementation: The method is simple to apply: one just needs country-level ESG data. Janardanan et al. use publicly available data (UN HDI, Transparency International’s CPI, carbon emissions). Other researchers or practitioners could adopt similar top-down scores for any derivatives whose underlying economics tie to geographies (currencies, stock index regions, etc.). This simplicity makes the approach transparent and replicable.

Limitations and Risks:

»

Data and Proxy Issues: The framework relies on coarse proxies. For example, E uses broad national emission averages and production weights; this ignores efficiency differences or corporate mitigation efforts. Similarly, S and G use country averages, which may misstate the actual producers of a commodity (e.g. global oil companies are not evenly spread by country GDP). These proxies may also be stale or lack corporate detail. Thus the ESG “score” attached to a futures contract is approximate, and might sometimes mis-rank contracts.

»

Market Impact and Risk Premia: If many investors pursue identical ESG screens, the flows could distort futures pricing. This may either erode expected returns or create volatility. For example, if speculative (non-hedger) demand shifts away from high-emission futures, the price may rise (or the roll yield fall), reducing the reward for whoever does take the short side. In effect, the classic commodity risk premium could be altered. Moreover, an abundance of ESG-driven demand could amplify momentum/technical trading and detach prices from fundamentals.

»

Traded Volume and Contract Design: Some futures already have relatively low open interest. If an ESG fund avoids or underweights a thinly traded contract, it could make that market even less liquid, which paradoxically might hurt other hedgers. Conversely, concentrating on a subset (the “top 50%” by ESG) could heighten positions in a few contracts, potentially creating concentration risk.

»

Fragmented ESG Goals: Investors have varied ESG objectives. Janardanan et al. show one can reweight E vs S/G in the composite score . But different goals (e.g. climate vs human rights vs corruption) may conflict, and a single ESG portfolio cannot maximize all. The authors note that the ESG-aware fund only achieves about 60–70% of the maximal possible gains in HDI and CPI scores (compared to dedicated S- or G- portfolios) . Thus it is inherently a compromise approach.

»

Regulatory and Reporting Challenges: ESG disclosure standards are evolving. Unlike stocks, commodity futures have no standard ESG reporting. Investors must interpret top-down metrics themselves, and regulators do not yet provide guidance (as noted, OECD/UNPRI have nothing for futures ). Without standard metrics, there is a risk of “greenwashing” (claiming ESG alignment without meaningful impact).

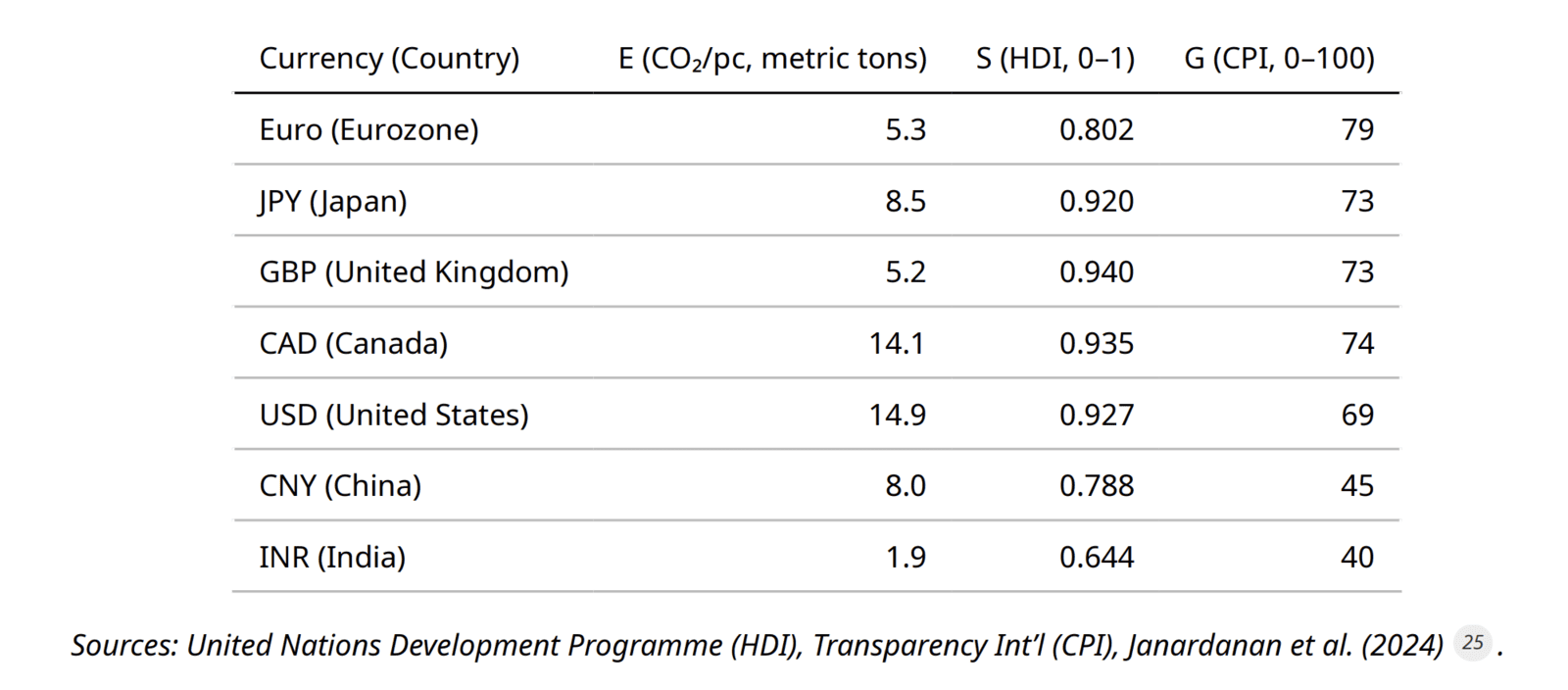

Other Derivatives Markets

The top-down scoring logic extends naturally beyond commodities. Foreign Exchange (FX) Futures: Multinational firms use FX futures to hedge currency risk, so one can score each currency by its country ESG profile. For example, currencies can be graded by per-capita CO₂ (environment), national HDI (social), and CPI (governance). Janardanan et al. tabulate ESG scores for major FX futures (Table 3) using UN and Transparency data. As a sample, high-emitting countries like Australia (E≈15, S≈0.946, G≈75) get a high E score (bad), while New Zealand (E≈7, S≈0.939, G≈87) looks better . These scores vary widely: e.g. the Indian Rupee has low HDI (0.644) and high CO₂ (E=1.9) versus Canadian Dollar (S=0.935, E="14.1)." One could then tilt an FX futures portfolio toward “greener” currencies. In fact, asset managers have begun explicitly linking ESG to currencies: J.P. Morgan, for instance, builds ESG frameworks that use environmental factors to capture commodity exposure and social/governance factors to forecast currency value .

Stock Index Futures: In equities, ESG integration is already common at the index level. For example, CME Group now trades an E-mini S&P 500 ESG futures contract. This contract tracks the S&P 500 Scored & Screened index, which filters out companies based on ESG criteria . The futures’ pitch is clear: “align your financial goals with ESG values” while maintaining a “similar return profile to the S&P 500” . In other words, investors can hedge equity exposure via an ESG-labeled index. Similar products exist for Europe (e.g. S&P Europe 350 ESG futures). Extending the commodity approach, one could also make regional stock index futures ESG-aware by weighting each country or sector by its aggregate ESG footprint (analogous to the country-weighted HDI/CPI method).

Commodity Swaps and Options: Beyond futures, OTC derivatives can incorporate ESG triggers. For instance, a commodity swap might have a carbon price adjustment: if a carbon index rises, the swap payoff shifts. Some banks now offer ESG swaps where collateral or payout depends on an issuer’s ESG rating 【15†】. While nascent, these instruments show that derivatives markets are beginning to blend risk management with sustainability goals.

Conclusion

Janardanan, Qiao, and Rouwenhorst (2024) make the case that ESG need not be confined to equities and bonds. Their ESG-scored futures framework shows investors can tilt commodity and FX portfolios toward preferred sustainability profiles with minimal disruption to returns. The empirical results – large reductions in carbon footprint and modest gains in social/governance metrics with little drag on performance – suggest feasibility. Crucially, the economics differ from firm-based ESG: it is about hedging costs and risk sharing, not capital funding.

Nonetheless, ESG derivatives integration has trade-offs. The liquidity and diversification benefits of futures tend to remain intact , but market distortions and data limitations are real concerns. The effectiveness of such strategies in changing real-world emissions is an open question, hinging on investor scale and market dynamics. Still, as regulators and investors push for broader ESG adoption, these derivatives approaches (top-down scoring, ESG-labeled futures) offer a plausible path. They complement existing ESG methods and can be applied to other markets – from FX to equity indices – with the same principle of scoring economic activity.

Table 2. Example Currency ESG Scores (Janardanan et al., 2024). Each FX future is assigned: E = national CO₂ per capita (higher = worse), S = country HDI (higher = better), G = Corruption Perception Index (higher = less corrupt).

Source & Reference

1. Janardanan et al. (2024) “ESG and Derivatives” (Financial Analysts Journal) along with CFA Institute and industry publications . The Janardanan framework is compared with other ESG approaches (Ausrice, AQR ), and additional data (currency ESG, index futures) are drawn from UNDP, Transparency Int’l, and exchange sources. All cited insights are drawn from the references above.

2. ESG and Derivatives | Financial Analysts Journal https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/research/financial-analysts-journal/2024/esg-and-derivatives

3. Commodity Futures and ESG | Portfolio for the Future | CAIA https://caia.org/blog/2022/01/11/commodity-futures-and-esg

4. aqr.com https://www.aqr.com/-/media/AQR/Documents/Insights/White-Papers/AQR-Sustainable-Commodities-Investing.pdf?sc_lang=en

5. Commodity Investing in the Age of ESG and Inflation by Brennan Basnicki, Tim Pickering :: SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3961718_code4879775.pdf?abstractid=3947377&mirid=1

6. E-mini S&P 500 ESG Index Overview - CME Group https://www.cmegroup.com/markets/equities/sp/e-mini-sandp-500-esg-index.html

7. Currencies through an ESG lens | J.P. Morgan Asset Management https://am.jpmorgan.com/se/en/asset-management/liq/insights/portfolio-insights/currency/currencies-through-an-esg-lens/