Author: Evan Michale Brown

Abstract

Portfolio asset allocation is the cornerstone of long-term investment success. However, many investors and wealth managers rely on pretax account values when determining allocations, ignoring a critical element: taxes. Tax-deferred accounts like traditional IRAs carry latent tax liabilities, and this oversight causes asset allocation to drift—potentially significantly—from intended targets. This paper explores the mechanics of tax-induced allocation drift, demonstrates how it arises, quantifies its effects under various scenarios, and argues for the inclusion of after-tax valuation in portfolio management practice.

Introduction: Pretax Statements Lie

In financial planning, a dollar is treated equally across all accounts—Roth, traditional IRA, or taxable brokerage. But in practice, these dollars have different real-world values after taxes. A Roth IRA dollar is fully spendable, while a traditional IRA dollar might only be worth $0.70–$0.60 depending on one’s tax bracket. Ignoring this discrepancy creates what I refer to as tax-induced asset allocation drift.

Consider this: two accounts each report $1 million in value. One is a taxable account. The other is a traditional IRA subject to a 30% marginal tax rate in retirement. On paper, both show the same value. But in practice, only $1 million from the taxable account can be spent; the IRA only affords $700,000 after tax.

Yet most portfolio allocation software and advisor practices rebalance using pretax numbers. This leads to a fundamental misjudgment of risk, especially when certain asset classes—like bonds—are preferentially housed in IRAs for tax efficiency.

The Problem: How Taxes Distort Allocations

Asset allocation targets (e.g., 60% equities / 40% bonds) are designed around an investor’s risk tolerance and return expectations. These are risk-calibrated targets.

However, when portfolios are split between taxable and tax-deferred accounts, and only pretax balances are used, the effective exposure to risk assets may deviate significantly due to unequal tax treatment.

A Simple Example

Portfolio value: $2,000,000

50% in traditional IRA ($1,000,000), 50% in taxable

60% stocks, 40% bonds allocation

Tax rate on IRA withdrawals: 30%

Following conventional wisdom, the investor houses all bonds in the IRA to minimize tax drag. But the after-tax value of the IRA is only $700,000. When this is factored in, the portfolio shrinks to $1.7 million in effective spendable value, and the asset allocation shifts from 60/40 to 67% stocks / 33% bonds.

Result: A 7% drift—exceeding the conventional 5% rebalancing threshold.

Why This Problem Is Systemic

Most financial planning tools and custodial platforms do not offer tax-adjusted portfolio views. Wealth managers, despite optimizing for asset location, fail to correct for this invisible drift. While tools exist for tax-loss harvesting and capital gains budgeting, few consider forward-looking after-tax value.

This is particularly troubling because wealth managers are trained to obsess over small basis-point improvements. Yet a 5–10% drift in asset mix is routinely ignored.

Mechanics of Tax-Induced Drift

Taxes cause asset classes to lose value at different rates. Traditional IRAs are subject to ordinary income tax upon withdrawal. Taxable accounts often benefit from capital gains treatment or step-up basis.

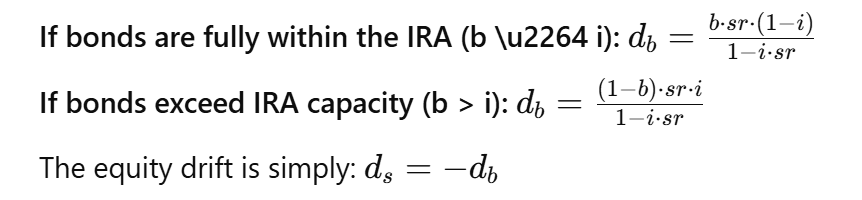

Let:

i = proportion of the portfolio in IRAs

b = target bond allocation

sr = marginal tax rate at retirement

The tax-induced bond drift is defined as:

Sensitivity Analysis: When and Where Drift Matters Most

We can break down portfolio drift by varying three key parameters:

Tax rate (12%, 24%, 35%, 43.4%)

Asset allocation (30/70, 50/50, 70/30 stock/bond)

IRA size as % of total portfolio (0% to 100%)

Findings:

Drift is highest when the IRA size matches the bond allocation.

Drift is zero when portfolio is all-taxable or all-deferred.

Drift grows non-linearly with higher tax rates.

At a 35% tax rate, a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio with 50% IRA exposure becomes 64/36 after-tax. That's nearly a 14% swing in effective asset exposure.

Risk-Reward Trade-Off Shift

Ignoring drift doesn't just affect exposure—it worsens the return profile. For example:

Pretax Portfolio:

Expected Return: 6.50%

Volatility: 11.49%

Sharpe Ratio: 0.57

After-Tax Portfolio:

Expected Return: 6.07%

Volatility: 11.87%

Sharpe Ratio: 0.51

The portfolio becomes riskier with lower efficiency.

Implications for Practice

Private Wealth Advisors should:

Use after-tax adjusted values in reporting and allocation models.

Monitor drift using a 5% threshold, just as with standard rebalancing.

Educate clients about the real value of retirement assets.

Software Developers should:

Build after-tax tracking tools

Enable visualization of spendable wealth by account

Add tax-aware rebalancing models

Regulators and Certifying Bodies (e.g., CFP Board, CFA Institute) should:

Encourage industry standards for after-tax asset reporting

Promote research on after-tax optimization

International Relevance

The challenge is global. IRAs in the U.S. have international analogs:

Canada: RRSP

UK: SIPP

France: PER

Japan: iDeCo

Poland: IKZE

Wherever retirement accounts defer taxes, this problem arises. Asset allocation drift due to taxes is a universal retirement planning hazard.

Limitations and Future Work

This analysis assumes:

Two-asset portfolios (equities and bonds)

Static tax rates

No RMDs, Roth conversions, or future tax law changes

Future research could explore:

Multi-asset class impacts

Incorporation of human capital

Dynamic withdrawal and spending strategies

Tax-aware liability-driven investing (LDI)

Conclusion: Pretax Precision, Post-Tax Deception

Taxes silently distort the risk profile of portfolios by changing the relative weight of each asset class. By ignoring the latent tax burden of IRAs and other deferred accounts, investors may find themselves misaligned with their true risk preferences.

The magnitude of this drift often exceeds common rebalancing triggers and materially alters both risk and return expectations.

For those managing retirement wealth, failing to account for tax-induced asset allocation drift is not just a missed opportunity—it is a misstep that can jeopardize long-term financial security.

The fix is simple: measure what matters. After-tax value matters.